The below-grade sealing of water intrusion at the building enclosure from the subsoils surrounding the structure should occur at an early stage in many construction projects.

However, the challenges of many below-grade situations are often overlooked and underestimated. Yet, the penalties for making mistakes during this critical step in the sealing process can be severe. Designers should fully understand the different mixtures of below-grade waterproofing materials for each project location and situation.

Since 1932, Architectural Graphic Standards (AGS) has provided architects with the most current design practices and standards. In a fast-paced, competitive industry in which innovation and knowledge is the key to success, AGS Online is able to continuously provide updated technical and design information.

“Below-Grade Waterproofing” is an example of the newest information you’ll find in AGS Online and reflects the current standard of care in building design for this subject. You will find building code considerations, material types, and different methods of achieving a dry building upon final construction.

BELOW-GRADE WATERPROOFING DETAILS

Careful consideration with the selection of the materials and methods specified to achieve the waterproofing results are encouraged during the design as well as field observation stages of the ultimate project. Due to the importance of a waterproofing system, it is most often applied directly to the structure with full contact or adhesion as this method alleviates water travel if a foundation leak is to occur.

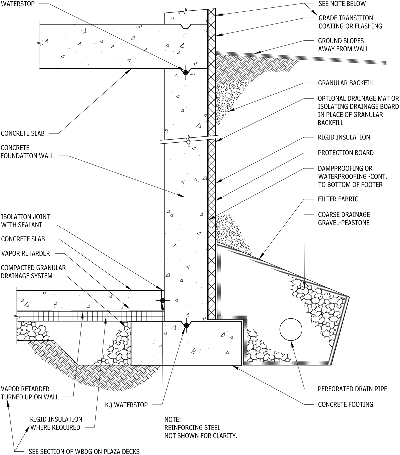

Typical below‐grade waterproofing systems are often made up of multiple elements, which include below‐slab and below‐footing vapor barrier, insulation, drain board, foundation drain, waterstops, protection board, filter fabrics, and clean wash stone. Although not all of the aforementioned pieces are required within every system, the designer should carefully consider the ability of the designed system and its prescribed components to not only prevent moisture from penetrating the foundation but to alleviate the hydrostatic pressure imposed upon the system.

Face‐applied waterproofing is often considered standard waterproofing by many as it is the act of applying the waterproofing system to the foundation wall on the exterior (weather) side prior to the backfill of the excavated soils. The waterproofing membrane should continue unbroken from the face of the footing to the top of the footing to above‐grade level, and typically be lapped behind the water‐resistant barrier (WRB) of the above‐grade wall control layer. The remaining layers of the system are installed per the instructions of the manufacturer in order to comprise a tested and complete system. See this diagram for an example of a typical foundation as it relates to below-grade waterproofing.

BELOW-GRADE WATERPROOFING VS. DAMPPROOFING

Although many designers assume that all below‐grade elements to structures with conditioned space within them should be waterproofed, that is not necessarily the case. The International Building Code (IBC) Section 1805, “Dampproofing and Waterproofing” provides the designer guidance as to when foundations should receive which type of treatment. Specifically, Section 1805.2, “Dampproofing” states, “Where hydrostatic pressure will not occur as determined by Section 1803.5.4, floors and walls for other than wood foundation systems shall be dampproofed in accordance with this section.”

Dampproofing is generally provided to reduce or prohibit the absorption of condensation and high‐humidity into below‐grade concrete or masonry and to reduce the likelihood of water not under a head of pressure from moving through or up the construction. Examples of applications requiring dampproofing include on the back side of site retaining walls or at basement walls where there is no head of water. Dampproofing is not “water‐tight” and will not perform to the same levels as waterproofing, and so should not be used in applications that require waterproofing.

SPECIFYING BELOW-GRADE WATERPROOFING

According to a 2005 article from The Construction Specifier, “while there are many excellent systems in the marketplace that can be specified and installed, the key point to success is understanding the benefits and limitations for any particular system.” The article goes on to state that, as is the case for virtually any part of a construction project, good planning and design will pay dividends in the long run. The excavation and replacement of a failed system can be costly in a number of different ways. Warranties, which can run anywhere between five years and 20, should be checked, and “proper design inspection is imperative for all systems no matter what guarantee or warranty is provided.

THE IMPORTANCE OF DRAINAGE IN WATERPROOFING

Keeping water out is obviously tantamount to waterproofing your below-grade space, but a key component of that is helping to keep the water away. As such, proper drainage of the subsoil in and around the foundation is key. Per the National Concrete Masonry Association, “Draining water away from basement walls significantly reduces the pressure the basement wall must resist. This reduces both the potential for cracking and the possibility of water penetration into the basement if there is a failure in the waterproof or dampproof system.” This can be done with perforated pipes or drain tiles, drainage pipes, landscape elements, and properly installed and positioned gutters and downspouts.

Soil, similar to water, exerts pressure on the back face of basement walls. The pressure exerted by water is equal to the density of water times the depth. Soil also exerts pressure in proportion to the density of the soil times the depth of the wall. This proportion is based on an earth pressure coefficient, which is dependent on the type and magnitude of soil movement and flexibility of the wall. It is important to understand these influences before designing retaining walls.

Four types of soil pressure need to be understood and resisted by retaining walls: active, at‐rest, passive, and surcharge.

The NCMA also stresses that construction methods, particularly properly tooled mortar joints, will aid in the below grade waterproofing effort for any foundation. “Properly tooled mortar joints help prevent cracks from forming, and contribute to the watertightness of the finished work.”

Since 1932, Architectural Graphic Standards (AGS) has provided architects with the most current design practices and standards. In a fast-paced, competitive industry in which innovation and knowledge is the key to success, AGS Online is able to continuously provide updated technical and design information.

“Below-Grade Waterproofing” is an example of the newest information you’ll find in AGS Online and reflects the current standard of care in building design for this subject. You’ll find building code considerations, material types, and different methods of achieving a dry building upon final construction.